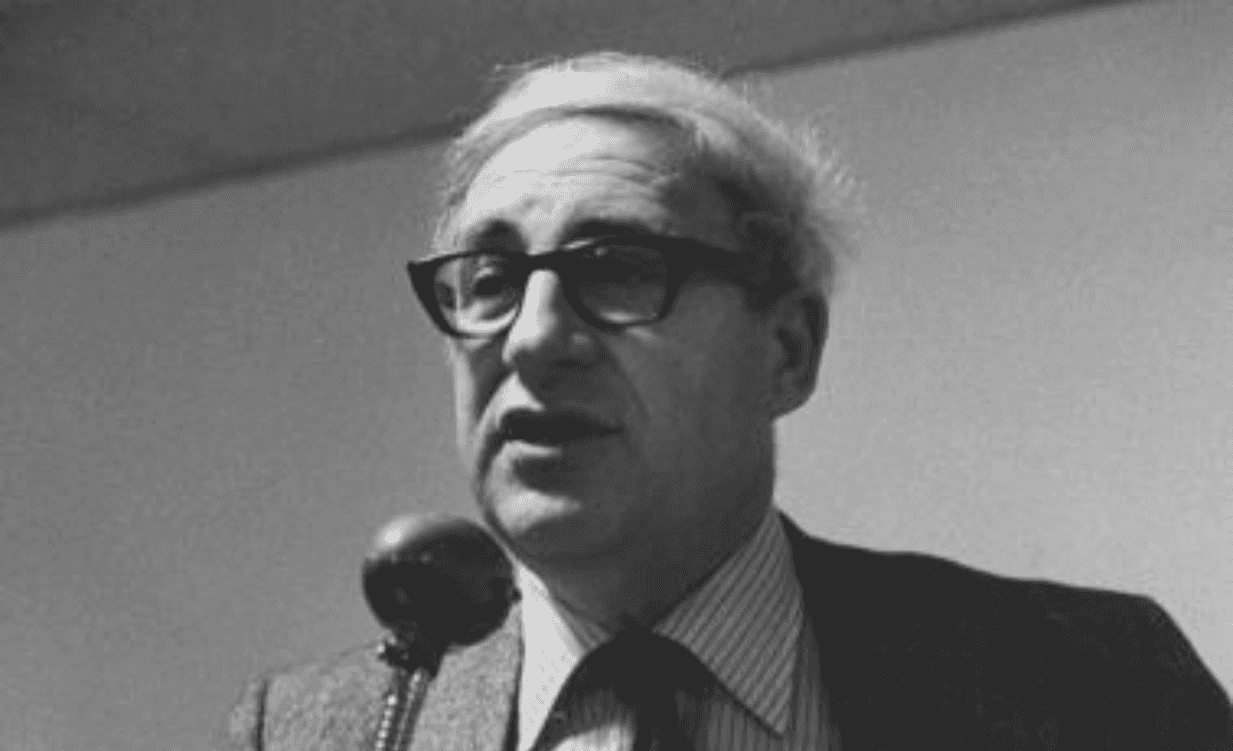

About Earl

Earl Raab was the longtime executive director of JCRC Bay Area, a highly prolific author of both books and articles, and a leader in American Jewish life for more than 50 years. Below are remembrances by Rabbi Douglas Kahn, William Kristol, and Phil Bronstein.

Dean of Community Relations

Remembrance by Rabbi Douglas Kahn, adapted from his introduction to the 1996 Interviews of Earl Raab by Eleanor Glaser, Courtesy of Regional Oral History Office, University of California, Berkeley.

He was known simply as the “Dean of Community Relations.” Not just in San Francisco, but throughout the country. Earl Raab made a permanent contribution to the lexicon of Jewish community relations.

His reputation as “the dean” was not only–or even primarily–because of his longevity in the field. He served as executive director of the Jewish Community Relations Council from 1951 to 1987 and continued to be involved as a consultant. Rather the term stems from his singular ability to cogently analyze the most complex issues facing the Jewish community, to articulate the exceptional aspects of the American Jewish experience, and to identify and implement necessary remedies to safeguard the status of Jews here and abroad.

His intellectual qualities remain legendary in our national organization, the Jewish Council for Public Affairs, formerly known as the National Jewish Community Relations Advisory Council. Every time our national organization meets it is absolutely certain that at least one major speech will make reference to one of Earl’s ideas about “a certain kind of America” which is good for Jews. Raabisms, I like to call them.

And, his mediating qualities were legendary here at home. Earl was a craftsman–of ideas, language, and viewpoints. He had the extraordinary ability to listen to differing views, and, without pause, to identify common ground from which to mold a united policy–on church/ state issues, anti-Semitism, Israel, civil rights, or any other issue that had the potential to divide the community. Part of the secret to his success was to get all sides to believe that he agreed with their viewpoint without his ever misrepresenting his own views or compromising his principles. Jewish liberals were confident that Earl was a like-minded liberal. Jewish conservatives were equally convinced that Earl was a kindred spirit. In fact, Earl, a veteran of the City College of New York Jewish Trotskyite club (the anti-communist left), with Irving Howe and Irving Kristol among the other luminaries, emerged as a very independent-minded moderate.

Intellect and integrity were one-half of Earl’s extraordinary package. The other two main elements, in my opinion, were productivity and local experiences.

Earl was an astonishingly prolific writer. In addition to his highly acclaimed books, with which he frequently collaborated with Seymour Martin Lipset, he wrote hundreds of articles, and thousands of background pieces which influenced generations of Jewish communal professionals and lay leaders. Watching Earl sit at his beloved Underwood Noiseless–and later on the computer–was equivalent to watching Picasso paint–both in quality and volume.

Indeed, Earl’s ability to portray the political landscape for American Jews is second to none.

Earl’s inspiration came from the local scene even while always retaining a passion for America’s role in foreign policy. Often sought for national posts in the Jewish community that would have required a move to New York, Earl instead relished the front lines and the day-to-day interaction between the Jewish community and other groups. The real issues provided the fuel for his fertile mind.

An Almost Legendary Figure

Remembrance by William Kristol, Founder and Editor of The Weekly Standard, 1995-2018

Earl Raab was an almost legendary figure in my youth. Since they lived all the way across the country, I didn’t see Earl and Kassie as often as I did some of my parents’ other oldest and closest friends. But I do remember how happy my parents were to see the Raabs when they did visit. There was a kind of closeness in their friendship that struck me as remarkable even as a kid. I remember Earl and Kassie and my mom and dad sitting in the living room and talking for hours in a way that was both utterly relaxed, as close friends can be, and very lively, as interesting minds can be.

It wasn’t just that my parents were so fond of Earl. I also remember how much my parents admired him. My father, I think, respected Earl’s judgment and wisdom more than almost anyone else’s. And in re-reading some of Earl’s writings, I see why. He had a kind of measured view of things that’s always been rare, but certainly has become rarer as time has gone by. In looking through a few of his writings I happened, for example, upon this, from a talk Earl gave in November, 1980, a discussion of the danger of anti-Semitism and its relation to a society’s broader predilection to extremism:

“There is the question of whether a society has enough built-in democratic traditions and restraints to withstand the blandishments of extremism, the disruption of democratic procedures, in the face of such dislocations. That is where the idea of America comes in. After all, the frozen, non-negotiable polarization of political opinion is, in a practical sense, the antithesis of the American idea and the vehicle for everything we fear.”

Still relevant and thought-provoking, to say the least. And a reminder that later generations, who never had the privilege of meeting Earl and talking with that kind and wise man, can still learn a lot from reading him.

My Mentor. And My Friend

Remembrance by Phil Bronstein, former Senior Vice President and Executive Editor, San Francisco Chronicle, and Chair of the Board, Center for Investigative Reporting

Earl Raab, well into his nineties, with not nearly enough time left on earth, took a trolley from his hilltop home, disembarked and walked through the most crime-ridden block in San Francisco for what would be the last of our lunches together.

Earl was my mentor of several decades. And my friend. But I was only one among many beneficiaries of his incandescent mind and fierce belief in the redemptive power of Community. He understood the world as well as anyone I’ve ever met, but fretted that in his almost 80 years of wisdom and writings, ever more relevant today, he somehow had not done enough. Or not done it exactly right. It was one of the very few things he was wrong about.

He believed in and fostered strong and engaged communities as the bedrock of sanity, fairness, dignity, compassion and good government. His battle was against toxic polarization, ugly tribalism, and authoritarianism. He had seen plenty of darkness throughout the American century and warned as early as 40 years ago that the pendulum was swinging back that way.

So he continued relentlessly as a warrior against ignorance and isolation, a champion for reason. “It’s not just to fight something but to build something,” he said. His search was always for what knits people together, not pulls them apart. He also acknowledged that, despite his calm and empathic temperament, “worrying (is) a Jewish art” he practiced.

He could be sly and he was complex. I infuriated his colleagues in the early 70’s by writing about a secret Arab and Jewish leaders meeting he’d organized. He just chuckled, winked at me and understood that a vibrant and adversarial press was one piece of the kind of democracy he believed in.

He took precious care with his extended family as its own small, vibrant community. He adopted me into that world rich with scholarship, raucous Friday night dinners and commitment to improving the world. His kids and grandkids carry on that commitment; they are in public policy, humanitarian work, the arts and journalism, among other places. In them you can hear strong echoes of Earl.

That day, in San Francisco, over Chinese food, he looked at me through his Swifty Lazar glasses, his ubiquitous chewing cigar within reach. We talked about the tribulations of age, and he scolded me for my own regrets though he shared some of his own. He laughed and reminded me he was 30 years older and still going. He had two books in the works, including an autobiography.

How, after all, do you articulate such a long, rich and consequential life? I have the answer, Earl: You’ve left us a legacy that continues to educate and inspire. That’s the grand gift to a just world of your time on earth.